Profile Of Henri Salaun

by Rob Dinerman

July 5, 2002 -In the 96 years since the USSRA began holding its national championships, no figure has made nearly as many appearances on its champions roster over as long a period as Henri Raoul Salaun, the stylish French-born shotmaking artist and four-time winner ('55, '57, '58 and '61) of the U. S. Nationals, an event he played in from 1950, when as an unheralded and unseeded entrant he almost knocked off the fearsome Diehl Mateer in a five-game second-rounder, through 1966, when, just months shy of his 40th birthday, he turned back the clock in a magical run to the semis.

In addition to his quartet of titles, Salaun reached the Nationals final in '51, '54, '56, '60 and '64, losing by one point in the fifth to Ed Hahn in '51 and in five games to Mateer (whom he led two games to one) in '60, and advanced to at least the semis no fewer than 10 times, including an eight-year run from 1954-61, even though he was forced by injury to withdraw twice during the 1960's.

He also won the first-ever North American Open championship in 1954, defeating Hashim Khan 15-14 in the third and last game of the final, as well as a record six Canadian Nationals (four in a row from 1956-59), a record seven Harry Cowles Invitationals, two Gold Racquets titles and a combined 26 USSRA age-group championships, a total which, like his 39 individual victories in the annual Tri-City (New York, Boston and Philadelphia) Lockett Cup competition, dwarfs that of everybody else.

Salaun's loss to Bill Wilson in the final of the 2002 USSRA 70-and-over tourney at the Harvard Club of New York this past February occurred a staggering 51 years after his inaugural appearance in a USSRA Nationals final, representing a time spread that no one has ever come close to duplicating.

That long-ago beginning may have been the most exciting Nationals final in the nearly century-long history of this event. The 24-year-old Salaun, playing in just his second Nationals, defeated Harry Conlon (who would win this crown one year later), Jack Isherwood and a somewhat past-his-prime Charlie Brinton, who had won four consecutive Nationals in the early- and mid-1940's, to reach the final.

There he went up against the 38-year-old defending champion Ed Hahn, who had attained that stage via a semi-final win over Roger Bakey of Boston in the semi-final match preceding Salaun's balancing match with Brinton. Midway through his four-game victory over Brinton, Salaun broke a string in the only racquet he brought to Chicago and had to finish that match and play the final with a racquet he borrowed from the by-then-vanquished Bakey, whose racquet was much more tightly strung than what Salaun was accustomed to.

This was indeed an ironic development for someone who not too long afterwards started what would become a successful sports equipment company specializing in racquet sales, including a number of shoe models that bear the Salaun name, which latter fact indeed would cause him to be declared ineligible for two National 40-and-over tourneys in the 1970's for running afoul of the very strict-constructionist USSRA rules regarding professionalism at that time! In any event, Salaun never felt fully comfortable with Bakey's racquet, but still managed to grab a two games to one lead before falling way behind early in the fourth game.

At that juncture, Salaun's relative inexperience caused him to commit a tactical error that he still lamented in an interview decades later; had he pressed Hahn all the way through that fourth game, he quite possibly would not have been able to make up the sizable deficit he faced but he almost certainly would have forced his aging foe to expend valuable energy in closing out that game that he therefore would not have been able to draw upon in the decisive fifth. Instead, Salaun let the fourth game go and before he knew it the still-fresh Hahn embarked on a shooting spree early in the fifth, volleying a series of sharply-hit nicks and winners that brought him to a seemingly insurmountable 10-1 lead. Incredibly, Salaun responded with a combination of his own winners and some nervous Hahn tins as his once-huge margin steadily diminished that added up to a 12-3 run and evened the score at 13-all. After a Hahn no-set call and a pair of split points, the 1951 National Championship rested on a single simultaneous match-point. A nerve-racking series of cautious left-wall exchanges finally ended when Salaun tried to lob a tight Hahn rail back into play and, perhaps in part due to the unfamiliar tightness of his borrowed racquet, over-lifted the ball to such a degree that it soared just above the back-wall boundary, landing in fact in the first row of the gallery in the most unwelcoming lap of a friend of Salaun's who had placed a bet on him to win!

After a pair of subsequent five-game quarter-final Nationals losses to Carter Fergusson in '52 and to defending champion Conlon in '53, Salaun rode the momentum he had generated one month earlier in his '54 North American Open win over Khan to attain the first of what eventually became five consecutive appearances in the finals of the Nationals, with losses to Mateer in '54 and '56 more than counter-balanced by titles in '55 (when he defeated '53 champion Ernie Howard of Canada in the final), '57, when he avenged Mateer's previous pair of final-round triumphs over him one and three years prior and handily won the final fourth game after Mateer had saved two third-game match-points, and '58, when he again defeated Mateer in the final.

That latter tournament began inauspiciously for Salaun, whose title defense seemed doomed when he incurred a bad upper-respiratory infection earlier that week. He showed up at Annapolis very unsure as to whether he would even be able to play, an uncertainty that only grew when Navy's legendary coach Arthur Potter escorted him to the infirmary, where he was provided a potion that so jolted his system that later that evening in his hotel room the entire room seemed to be spinning crazily out of control. But ultimately he was aided by both the medication and a fortuitous draw that byed him through the first round and thus gave him additional time to rest. He barely got past Conlon, 15-13 in the fifth, after dropping the first two games, but was rejuvenated enough by the time he played Ray Widelski in the semis to win that match easily and follow that up with a close four-game final over Mateer.

Salaun and Mateer would face eachother in the finals of the '60 and '61 Nationals as well, with Mateer surmounting a two games to one deficit to defeat Salaun for the last time in '60 and Salaun earning a four-game victory the following year. All told, they split six National finals during the eight-year period from 1954-61. Mateer complemented his trio of National titles with North American Open crowns in '55 and '59, while Salaun won the '54 North American Open (and was runner-up to Roshan Khan four years later), plus his four National Singles tourneys.

Between them, they won every one of the 11 editions of the Cowles event from 1950-60 and all but one of the Canadian Nationals from 1950-59. Mateer buttressed his singles achievements with a record 11 National Doubles titles from 1949-66 with five different partners (Hunter Lott, Calvin MacCracken, Dick Squires, John Hentz and Ralph Howe), while Salaun has dominated the National age-group categories to a degree that, barring an absolute miracle, will never be approached, much less equaled.

Their extended rivalry at the very pinnacle of the amateur game must therefore most properly be ruled a draw, which in no way detracts from the fascination it came to acquire not only throughout the squash world but in the larger American community as well. This latter phenomenon was graphically symbolized both by the substantial article that appeared in Life Magazine during the winter of 1954 describing Salaun's unexpected 15-7, 12 and 14 win over Khan in the first-ever North American Open final and, perhaps more significantly, by the cover of the February 10th, 1958 issue of Sports Illustrated, which consisted of a close-up frontal photo of the two stars warming up before yet another final with the caption "Squash Champions Henri Salaun and Diehl Mateer."

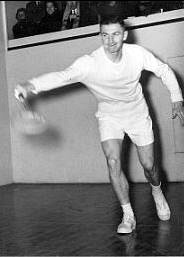

As often occurs when two top players become locked in an ongoing series of competitions for their sport's most revered trophies over a significant portion of their overlapping careers, the Mateer-Salaun rivalry developed a unique identity forged in large part by the substantial contrast that existed in personality and playing style between these protagonists. Mateer's game, like the man himself, was built along clean and classic lines and had an all-American golden-boy feel to it in the best sense of the term; blond, muscular and handsome, he was blessed with great power, size, mobility, touch and all-around athleticism, and his fundamentally sound strokes were developed in squash's mecca, the Merion Cricket Club in suburban Philadelphia. He was above all else a power player, who volleyed everything within his long reach and attempted, usually successfully, to physically impose his game on his out-classed opposition. Salaun, on the other hand, was small and lean, the personification of economical but effective footwork, who glided, seemingly effortlessly, to the ball and had as well the maddening capacity to place it just enough out of reach to avoid being cut off or retrieved.

He was probably the most astute strategist and counter-puncher in the game and his retrieving, patience, willingness to play long points and deft execution of lobs and front-wall shots (all of which seemed to die just before reaching the far side wall) provided potent antidotes to power players like Mateer, Howard and Stephen Vehslage, all of whom experienced varying degrees of frustration in their attempts to overpower their less imposing adversary with pure heat. Salaun lacked the thunderbolts these sluggers possessed, operating instead with the murderous aplomb of a dinner guest quietly pocketing his host's most expensive silverware.

Whenever he played Mateer, the leading representative of the power game, the question always was which exponent of these diametrically opposite playing styles would prevail on that particular occasion. The undulating quality this rivalry acquired during the 1950's and early 1960's, with neither player ever able to put together a winning streak that lasted more than a few matches, made the outcome of each of their final-round summits impossible to predict and imbued every one of their several-dozen meetings with a tenor of its own. What can be said with much more assurance is that Mateer had had his fill of high-level squash by the time he reached his mid-30's, while Salaun has maintained his interest all the way to his 76-year-old present. Whether this characteristic has its genesis in his difficult early years is subject to speculation.

Born April 6, 1926 in France, he was forced in 1940 at age 14 to flee the Nazis with his mother on a mine-sweeper that took them from Brittany to England, from which they took a freighter as part of a British convoy one year later to Halifax, Nova Scotia and eventually made their way to Boston, where they stayed for awhile with friends of his maternal grandfather, Dr. Raoul Coquelin, an avid tennis player, who was so inspired by a trip to the famed Roland Garros, the site of the French Open, one of the four Grand Slam events in tennis, that he built his own clay tennis court. Several of Salaun's uncles attained nationally rankings, and Henri excelled in this sport at Deerfield, the noted New England prep school where he spent his last two high school years, as well as in soccer and squash, which he discovered during his senior year and in which he rapidly improved. Salaun's paternal grandfather, the first of what has now become four generations of Henri Salauns, was a First Admiral in the French Navy during World War I and into the 1920's.

Though Salaun graduated from Deerfield in 1943, his time at Wesleyan was interrupted after his freshman year by two years of military service, where he was under the command of General George Patton, and he therefore didn't graduate college until 1949, having attained all-American status in soccer and tennis. His squash career began in earnest shortly thereafter and, as noted, by 1951 he had reached his first Nationals final, where he fell that one simultaneous match-point short in his rollercoaster fifth game with Hahn. He won his fourth and last Nationals exactly one decade later, conquering Mateer in the last Nationals meeting between these two titans on the latter's home turf in Philadelphia, but was prevented from defending in Buffalo the following year when he tore a plantaris muscle 10 days before the event was to begin and couldn't recover in time.

Two years after that, he emerged from a brutal five-game semi-final with Harvard senior star Victor Niederhoffer too drained to have anything left for his final with Niederhoffer's Yale contemporary Ralph Howe, who won in four games. A pre-tournament back injury that worsened dramatically after his first-round match ended Salaun's chances and forced him to withdraw at Hartford in '65, but one year later he engineered a glorious last hurrah in New York when he entered mostly as a favor to the tournament committee and to revisit the site of his triumph seven years earlier, and punctuated this appearance with a four-game upset win over the top-seeded defending champion Vehslage before bowing in overtime-in-the-fourth in the semis to Sam Howe. A glorious last hurrah for Salaun's Nationals career in the OPEN division, that is---he would win the 40-and-over throughout the first five years of his eligibility (1967-71) and six times overall, a figure which well might be even higher had he not missed those two years when he was declared ineligible.

In 1968, in fact, the Nationals was held in Boston, where Salaun has been based for the past several decades. He and his wife Emily co-chaired the event, the last Nationals to have a big (12-piece) band and a black-tie dinner, and Salaun's considerable administrative duties did not prevent him from defending his 40-and-over title with his second straight final-round win over tennis great Vic Seixas, who had won this flight from 1964-66. Then from 1977-81 he would similarly win five straight USSRA 50-and-over flights, and six of seven, and on and on it went.

There is no age-group category right through the 70-and-over which he hasn't won at least four times or at least twice in a row, despite medical maladies over the years ranging from elbow problems to rotator cuff surgery to a prostate operation. In San Francisco in 1983, in fact, he opted not to defend the 55-and-over title he had won in Washington the previous year, deciding instead to "play down" in the 50-and-over division, which he won in a highly entertaining though straight-set final against his longtime opponent Charlie Ufford, his adversary in a rivalry whose matches went both ways, though usually to Salaun, during their numerous battles in Open and age-group Nationals competition.

Both Ufford and Jay Nelson, another multiple Nationals age-group champion, cited Salaun's exceptional control of the pace, placement and spin of the ball when asked to identify the most formidable aspect of Henri's game. The drop shots died just that little bit closer to the front wall than anyone else's, the three-walls had a troublesome tendency to roll insolently out of the nick and the lobs, rails and crosscourts were directed just enough out of reach to undo an opponent's balance and court positioning.

Unlike so many of his contemporaries who have cashed in their squash and business chips long ago, Salaun today is still so busy with his sports equipment company that several interviews for this article had to be scheduled more than a week in advance to accommodate his brimming and travel-laden schedule. He has maintained both his playing weight and competitive ardor in both squash and New England tennis, in which he has enjoyed great success over the years as well.

He certainly remains as sharp, lively and feisty as ever, even to the point of voicing a contrary opinion at the general meeting at the most recent hardball Nationals in New York several months ago, which led to an interesting debate regarding the selection of future sites for this annual tournament. On this occasion and in many other ways, on and off the court, Henri Salaun continues to demonstrate the well-known and ongoing acumen and spirit that, along with his record-shattering list of achievements, have propelled him to the fully deserved status this first-ballot Squash Hall of Fame inductee has long since attained as one of the absolute leading figures in the history of American squash for more than half a century.

This first appeared on squashtalk.com

Back To Dinerman Archive

Main